THE 15 BEST FILMS OF 2015

Be it raging hitmen, dystopian chaos or the rasp of a conductor's disapproval, 2015 featured some outstanding trips to the cinema. Here are the best ones.

15. John Wick

Something of a surprise package, this ferocious debut from co-directors Chad Stehelski and David Leitch sees Keanu Reeves tearing his way through an army of evildoers, his eponymous avenging angel hunting those who killed his dog and stole his motor. The leading man remarkably casts aside that dross littering his résumé since the spectacular success of The Matrix.

Uncompromising, unspeakably ruthless, Wick explodes from the frame, the roiling mass at the centre of a rippling and brilliant thriller. It eschews pulpy B-movie tropes for a gorgeous neon-drenched milieu that reaches visceral high watermarks once thought lost to mainstream American cinema. Possessed of near balletic gunplay and a current of savagery lingering beneath the sheen, this is a forceful precursor to an inevitable sequel.

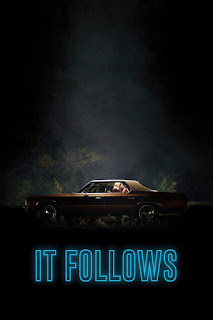

14. It Follows

In David Robert Mitchell’s steady grasp, It Follows is rendered a terrifying, relentless contemporary chiller, ripe with a sense of cool and a charge of intense foreboding that runs throughout its confidently glacial progress. As a band of terrified teenagers pass a hex between themselves via the sexual contact that they otherwise crave, the anonymous poltergeist-cum-demon-cum-angry-spirit hunting them could be forgotten in a less assured picture.

Driven by a curiously evocative electro score that recalls the synthy menace of John Carpenter’s finest work, this is gripping fare exploring surprisingly profound themes, skirting around convention without succumbing to it. If a filmmaker of Mitchell’s considerable stylistic talents can resist the allure of the mainstream, there should be many more scares in store.

13. Selma

This handsome civil rights tale is far from a flawless product but its greatest strength rests in a comprehensive emotional resonance. Director Ava DuVernay underplays sensibly, allowing the subject matter to speak for itself and her portrait of a bleak time arouses horrified awe almost from the beginning.

Tugging at the corners of modern civilisation’s guilt, DuVernay finds a noble avatar in the increasingly adaptable form of David Oyelowo. As Martin Luther King, he draws humanity, both real and inspiring, from a character most will only ever know by his deeds. This preacher-activist’s non-violent approach to demanding fairness made him no less a despised individual in the sneering, sweat-soaked, racist South, but Oyelowo, fascinatingly, adds a dash of cold-eyed political manoeuvring to King’s aspirations on the hallowed turf of the eponymous battle ground.

12. Spectre

In following up his previous Bond outing, Skyfall, auteur-cum-big-budget-helmer Sam Mendes chooses a new tack. He shifted tone from the cold fury that marked his first film to a truly hot-blooded affair, one imbuing his leading man with humanity, myriad flaws and a significantly extended backstory that goes far beyond the largely ambiguous hints that have peppered Daniel Craig’s tenure until now.

Spectre is no dour tragedy, of course, but Bond is a serious man for a serious world. As with the other post-Bourne instalments, he constitutes a coiled and dangerous creature, increasingly synonymous with the millennial strut that Craig, in all his silent, hard-drinking forcefulness, lends to a figure not quite up to speed with modernity. As a touchstone for an established franchise, his is a necessary presence in grounding the spectacular scenery and sleek, occasionally brutal action sequences. How Craig finally bows out next time round will be fascinating.

11. A Most Violent Year

As with Margin Call and All is Lost, J.C. Chandor tells a big story from a position of intimacy in A Most Violent Year. His forbidding and artfully conceived tale plays out on a canvas grander than before, namely the feted, nebulous, arguably unattainable American Dream. This is what is at stake as Oscar Isaac’s hard-grafting immigrant tycoon Abel Morales wagers money and reputation to move up the social ladder before it is pulled from his grasp.

With a hypnotic Jessica Chastain by his side, Morales’s pursuit of elevation proved too slippery for the Academy. The film was snubbed in every major category for February’s Academy Awards, a baffling decision given its dark muscularity and unflappable pedigree. Chandor’s subtleties, his abundance of wintry greys, suggest that this is far from the conclusive masterpiece normally lauded by the establishment. It’s their loss.

10. Beasts of No Nation

10. Beasts of No Nation

Nobody should be put be put off by the small-screen origins of Cary Fukunaga’s drama, which debuted to a worldwide audience on Netflix (its principal distributor) in October. There is nothing inconsequential about this adaptation of the 2005 novel by Nigerian author Uzodinma Iweala, a beautifully realised portrait of chaos and lost innocence in one hellish corner of planet Earth.

The movie centers on the travails of a young boy (Abraham Attah) who, in the midst of a civil conflict in an unnamed West African country, falls in with a battalion of zombified child soldiers led by Idris Elba’s Commandant. Fukunaga proves equally adept as writer, cinematographer and director, conjuring a brave, arresting, and ultimately haunting movie that does not shirk from the abject horrors of war. The cast, too, led by the charismatic Elba, excels in conveying the gamut of human frailties so inherent to the species.

9. Brooklyn

Colm Tóibín’s acclaimed literary source material is brought to life by director John Crowley and the increasingly transcendent Saoirse Ronan. They elevate this elegant story of diaspora and nationhood to a level above the tweeness that can so often invade the annals of Irish America’s formative experiences.

Shot through with restraint and a maturity belying potentially maudlin stylings, Brooklyn displays a rare ability to affect even the most hardened souls, its undercurrent of hope mixed with longing for home playing out through the experiences of callow Eilis Lacey (Ronan). Her search for a place to belong is the fuel of emigration itself, but Crowley crafts a narrative of such poise that this seems less like a teary melodrama than a deft commentary on the ties that bind us all together.

8. Wild

In spite of her status as a staple of the gossip pages, Reese Witherspoon has always remained a gifted performer regardless of the genre — witty, passionate, engaging. That said, in Wild, Jean-Marc Vallée’s follow-up to Dallas Buyers Club, Witherspoon is pushed to the outer limits of her talent, both physically and emotionally. She emerges on the other side bloodied but unbowed, boasting a career-best portrayal of a person brought to the edge through the nudging of her own demons.

This adaptation of Cheryl Strayed’s 2012 memoir about her self-discovering quest along the mighty Pacific Crest Trail wields beautiful photography, breathtaking scenery and a sincerely affecting account of sturdy endurance in the wilderness. Yet, Witherspoon rises above it all, eliciting sympathy with a performance of stark honesty, equally startling and rewarding.

7. Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance)

Art imitates reality as Michael Keaton strives for a career rebirth in Alejandro González Iñárritu’s powerhouse satire that mixes black comedy and surrealism to a heady degree. The deserved winner of this year’s Academy Award for Best Picture, Birdman’s strength lies in its relentlessness, its audacious mechanics never letting the audience settle into a groove.

Keaton plays a faded star who craves professional respect via his self-directed Raymond Carver adaptation on the Broadway stage. Iñárritu chronicles every insecurity, every backstage clash, every slip into mediocrity with an unblinking focus on his star’s twitchy has-been. Filmed, save for a brief interlude, in one apparent take (it isn’t), this is a singular, important study of hubris run amok.

6. Ex Machina

Screenwriter and novelist Alex Garland’s directing debut, Ex Machina, is a chilled exploration of the male-female dynamic, which unfolds through the prism of noirish sci-fi, all glistening surfaces and whirring smart technology. A sophisticated adult fable about three immature beings, Garland’s project channels Frankenstein in questioning the limits of mankind’s unending scientific evolution.

When programmer Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson) wins the chance to spend a week at the vast eco ranch of his boss, software magnate Nathan (Oscar Isaac — think Dan Bilzerian with a genius intellect), his task is to test the latter’s newest invention: a robot named Ava who bears the exquisite features and grace of Alicia Vikander. Caleb is on hand to carry out the Turing test on the humanoid, thus establishing the scale of her sentience. The resulting interplay between the leads is entirely unsettling, Nathan’s ulterior motives as obvious as Caleb’s hidden depths are unexpected. It is Vikander, however, who shines with an ethereal autonomy that bewitches and unnerves in equal measures.

5. Sicario

Emily Blunt may not be the first actress who springs to mind when imagining a dowdy FBI rescue specialist plagued by exhaustion and a pulseless love life, but in Sicario, Canadian filmmaker Denis Villeneuve’s border-crossing thriller about the US's endless war on drugs, the usually radiant star is every inch the tiny cog within the clanking gears. Villeneuve, utilising a similar palette to his terrifically accomplished Prisoners, weaves a web of shadows and obscurity that never comes close to the straightforward conceit at the heart of that latter work.

This is, instead, an infinitely more challenging picture. Featuring shifting realities, treacherous ethics and fluid allegiances, Sicario bursts with a dark, murky power both horrifying and chilling in its complexity. Such grey areas are best exemplified by Benicio del Toro and Josh Brolin, twin totems of America’s grimier business who, with unblinking acceptance, embrace the necessity of their respective existences.

4. The Martian

Ever the aesthete, Ridley Scott is no stranger to more intimate pieces, away from the blockbusting fare he is most famous for churning out. Matchstick Men, American Gangster and even, to a lesser degree, Alien were all films that relied on substance over spectacle. What a pleasant surprise, then, that Scott’s adaptation of The Martian, Andy Weir’s 2011 novel of the same name, should combine his fondness for human drama with the visual flair that has always defined him.

Starring Matt Damon as the astronaut stranded on Mars, Scott’s latest sci-fi is a vibrant and moving epic that beats with a heart every bit as affecting as the vastness of its crimson landscapes. In the midst of his alien exile, Damon’s Mark Watney is a vessel for our own inherent tendency for survival and while it lacks the existential conflicts of Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, The Martian — exhilarating, replete with significance and, crucially, very enjoyable — is no less soaring in its study of what mankind is apt to achieve.

3. Foxcatcher

In delving into the rather niche field of Olympic wrestling, stylish straddler of genres Bennett Miller (Capote, Moneyball) mines utterly exquisite contributions from a trio of actors one would not immediately throw together in pursuit of dramatic tension. A classic leading man (Channing Tatum), a comedian (Steve Carrell) and a chameleonic character actor (Mark Ruffalo) all merged to test each other in Miller’s true-crime take on the bizarre happenings at Foxcatcher Farm, the training base designed and funded by millionaire John du Pont.

Given that competition rests at its core, Foxcatcher’s three pillars cannot be separated, with Tatum (as Olympic gold medallist Mark Schultz) genuinely remarkable, steeped in pathos. Carrell jettisons that patented likeable shiftiness for a brew of psychopathy and petulance, a gauche fabulist placing himself at the centre of a world in which he will never belong. Ruffalo, meanwhile, portrays Schultz’s older brother, Dave, who battles to protect his own sanity. The latter, in particular, brandishes a rare streak of subtle adaptability and alters his voice and posture, even his gait, in a depiction that hits multiple emotional notes.

2. Mad Max: Fury Road

For all the abundant qualities exhibited by George Miller’s original Mad Max trilogy, its status as a somewhat cult staple in the dystopian canon, not to mention a 30-year absence from the zeitgeist, afforded the franchise’s newest entry, Fury Road, a relatively low-key arrival on the big screen.

That said, those intrigued by the continuing adventures of Max Rockatansky (Tom Hardy, replacing Mel Gibson) were promptly rewarded by a glorious, swaggering and kinetic injection of purified adrenaline that banishes memories of the rubbish that grabs our money, offering only Vin Diesel in return. Miller’s resurrection of his iconic character may be deranged, but it is executed with such panache — blistering set pieces fill almost every frame — that the beauty in the chaos is its own reward. A reminder that blockbuster cinema is still able to captivate, Fury Road was the kind of rush that the medium requires to stay true to itself.

1. Whiplash

On the face of it, an indie movie about jazz drumming at a haughty New York conservatoire does not immediately capture the imagination. In reality, however, sophomore director Damien Chazelle’s scorching psychological odyssey, Whiplash, fully justified the pre-release hype and firmly established itself as 2015’s best film.

While Miles Teller brings his own shifty charisma to the screen as the young drummer with an ambitious streak that feels less admirable than it does distasteful, it is J.K. Simmons who dominates. Simmons was rightly awarded an Oscar for his portrayal of band conductor Terence Fletcher and it is a performance of monstrous proportions — white-faced, black-clad, gimlet-eyed. Channelling every sneering teacher you ever wanted to punch but couldn’t, Simmons’s ferocity courses throughout this astonishing picture, carrying it to a place both dark and unimagined. Simply magnificent.